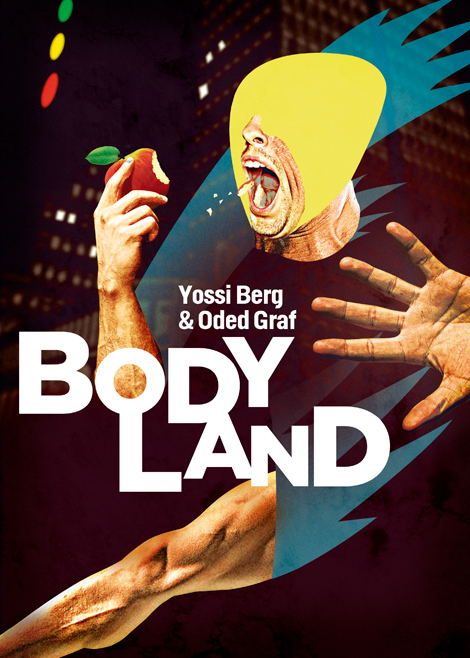

Yossi Berg and Oded Graf Turn the Body to a Crazy Territory

12/12/2013

In “Bodyland” join choreographers Yossi Berg and Oded Graf the trend that sees the body a place of political discourse, and suceseed to stand out with their unique voice and creativity

Many dance performances have been staged in Europe and Israel in recent years in which the body is seen as a site where history is written in movement, a site of political discussion. The piece “Bodyland” by Yossi Berg and Oded Graf, which premiered this week at the International Exposure Festival at the Suzanne Dellal Centre, joins these works engaged in sociopolitical criticism, but is unique in the surprising and utterly refreshing way in which the choreographers chose to convey their message. Berg and Graf picked the path of social criticism, but gave it a simple and enchanting interpretation, as physical as possible.

The piece is performed by five wonderful male dancers. Three are from abroad – Germany, France and Denmark – and two are Israeli. The French dancer spreads out his hands, swells his masculine chest with pride and declares, “I am France.” For the unbelievers he details the “body map,” divided into districts, and ends by touching his nipple, which he identifies as the spire of a municipality. After France, it’s Germany’s turn, then Denmark’s, and when little Israel’s turn arrives, one dancer is not enough; two are needed: Berg and Graf declare that their body is Israel, then roll up their pants, point down and say: “And that’s the Palestinian Authority.” They also say: “This is the Holy Land,” concluding that “our body is holy,” and regarding another bodily protuberance they say, “This is the Western Wall.”

This point of departure – of the body as territory, as a geographical map – creates a swirl of unexpected, humorous solutions. They are accompanied by short sentences about the meaning of various body organs, opening a wide field for critique and dialogue, and a settling of accounts with the past and present. The texts, meticulously chosen, touch on the bloody wounds of all countries. The diction is excellent, and all in all the piece is both funny and sad.

Berg begins the performance. He stands on the stage, places his hand on different body parts and calls them by name, presenting the repertoire of body parts. He does this using the accumulation method, meaning he begins anew each time and adds another item. This recalls Trisha Brown’s famous solo, in which the method is implemented with a combination of speech and movement. Berg completes the list by stretching his mouth wide open as if about to scream, but immediately a hand blocks the scream and all we can hear is a kind of SOS call: “Take these hands off of me.”

In the next scene, Berg is jumping a rope. He is joined by two others jumping to the same rhythm, sometimes in the same direction, other times as each sees fit. They look happy, displaying a masculine brotherly sportsmanship. “We are happy because we expect nothing,” says one of them, and the rope leaves trails of light in the air behind him.

Throughout the piece, the same motif returns of a crazy world in need of a psychologist. “But why go to a psychologist, if I don’t remember anything from my childhood,” say the athletes, cultivating their body while their soul is impaired. A huge inflated hand, coal-black, hovers above the stage, threatening to swallow the men, turning them into dwarfs and offering an alternative map to their bodies. This is the menacing fantasy. In between, encounters take place between the dancers, displaying their physical abilities. These are encounters between muscles, sweat, encounters that respond to the force of attraction. Yet although they allow the dancers to show off their technical abilities, they are not very interesting in terms of movement and are too long.

The artistic freedom to dare and bring together the dancers and their insane physical ambitions and the intelligent text, which illuminates and awakens reality, all as part of a fantasy about to swallow everything, creates a different kind of work from the one we are led to expect.

– Ruth Eshel, Haaretz

Photo Robin Hart