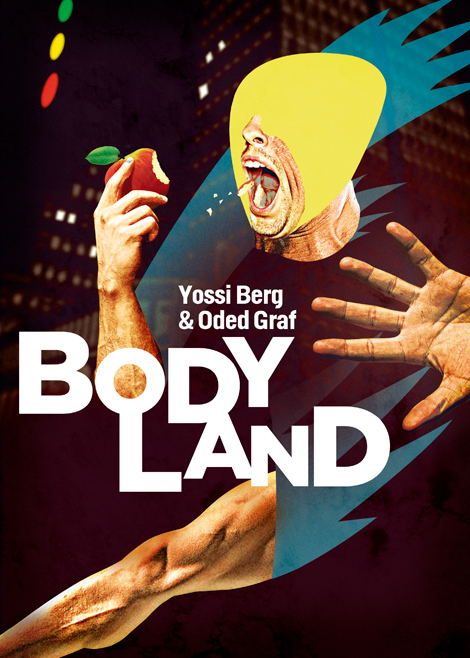

Bodyland: Zen and The Art of Deconstructing the Body

06/12/2013

Yossi Berg and Oded Graf continue to demonstrate an intelligent and fascinating creative voice, one that isn’t afraid of touching on political issues, yet doesn’t do it on the expense of movement being the prime source from which the materials are created.

Yossi Berg and Oded Graf stopped yesterday (Thurs) at Warehouse 2 in Jaffa, to present their new work Bodyland, a moment before they take off to Denmark, where they will continue their current tour of the work. Five men, including Berg and Graf themselves, make up the cast of this interesting work, that is very much a continuation of their previous works Animal Lost and Black Fairytale. Same as in both previous works, the choreography is layered with extensive use of text, set and props. Here too, the dance itself manages to articulate the political and philosophical ideas the makers were looking to convey in the work.

Bodyland opens with a monologue of Berg, detailing his body parts over and over again while moving (heart, head, cheek etc). Every cycle, a new body part is added to the list, giving the feeling of a simple animation created when flicking through pages rapidly, each time a new element is added to the image. The body, which is the centre point of this work’s exploration, is broken down only to be reconstructed anew. Berg and Graf wish to examine the problematic nature of the relationship between body and physicality on the one hand, and nationality and nationalism on the other. And perhaps even more so, it’s an examination of the way in which nowadays, a body is appropriated by so many discourses, and is subjected to such varied semiotic structures, that it’s almost hard to notice it beyond reading it in these contexts. In the work however, it doesn’t translate into a process of modern mourning of the natural body, or a romantic longing to return to what is in front or behind the words. On the contrary, in this work Berg and Graf manage to offer a critical viewpoint without offering a solution to the situation they are examining.

At the end of the monologue Rihanna’s song We Found Love is played, while dancers in shiny sporty attire come on with skipping ropes, forming exact geometric structures. In seconds the body is drawn into a different conversation, a new task, as if being asked to keep up a certain rhythm, to get in happy and become fit. Later on the dancers will tell of their countries of origin, while marking imagined landscapes of mountains or streets over their tummies and arms.

The question regarding the environments in which we grew up and its relationship to our personality, isn’t merely a sociological one. For Berg and Graf it’s essentially an ethical one, that critically examines the way in which our relationship with our body is already mediated via a set of values, symbols, and cultural, national visual imagery.

As always, the texts given to the dancers are filled with much humour, especially one that is self-directed.

The performers in Bodyland aren’t busy with dancing ‘pretty’ or ‘elegantly’, since the choreography itself doesn’t demand it. In fact, the physical language is derivative of the ideas themselves, and isn’t bound by one vocabulary. Sometimes the body is loose and sloppy, limbs and body parts stretched out and thrown around, while other times the body is held tight, and appears strong. Being a rounded performance in the sense that it is created around one central idea, from which the movement, set, music etc, are derived. The lack of unity in the performance styles becomes irrelevant.

Set wise, the designers used giant silver balloons, shaped like giant legs and hands. It was a parodic over exaggeration of our obsessive ealing with the body, however putting its aesthetic value aside, I’m not sure it was altogether needed. In other words, the composition stood firmly even without it. On the other hand, the usage of little balloons blown up and attached to Graf’s fingers was a gorgeous, original and befitting choice.

Yossi Berg and Oded Graf continue to demonstrate an intelligent and fascinating creative voice, one that isn’t afraid of touching on political issues, yet doesn’t do it on the expense of movement being the prime source from which the materials are created. And perhaps unlike the two previous works, Bodyland will be more easily digested by Israeli audiences. We can only hope they will stop over more often.

– Tal Levin , Achbar Online

Photo Robin Hart